Journal Home Page

OPEN ACCESS

The Effectiveness of User Interface Design in Business E-Communication

| Samiha Zaman Prima ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-7086-0005 Janjila Jahan Zareen ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9704-5288 Ummy Amerin Asha ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-7674-804X Md Adil ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-1062-6822 Department of Graphic Design & Multimedia Faculty of Design & Technology Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh |

| Prof. Dr Kazi Abdul Mannan Department of Business Administration Faculty of Business Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: drkaziabdulmannan@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-132X Corresponding author: Samiha Zaman Prima: samihavnc215@gmail.com |

J. polic. recomm. 2026, 5(1); https://doi.org/10.64907/xkmf.v5i1.jopr.3

Submission received: 3 October 2025 / Revised: 9 November 2025 / Accepted: 17 December 2025 / Published: 2 January 2026

Abstract

This paper investigates the effectiveness of user interface (UI) design in business e-communication. The study synthesises existing theory and empirical findings to propose an integrated view of how UI design influences the efficiency, clarity, trust, and outcomes of electronic business communication (email, enterprise collaboration tools, web forms, e-commerce checkout flows, and customer service interfaces). Grounded in human–computer interaction (HCI) principles, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), the paper develops a theoretical framework linking UI attributes (usability, information architecture, visual hierarchy, affordances, feedback, accessibility) to communication outcomes (message comprehension, response speed, task completion, perceived credibility). A qualitative research methodology is described for studying these relationships in business contexts, including semi-structured interviews, observation, and thematic analysis. Findings from a synthesis of qualitative studies and applied practitioner research are discussed, showing that well-designed UIs improve clarity, reduce cognitive load, increase user satisfaction, and enhance business metrics such as conversion and response rates. Key practical recommendations are provided for managers, designers, and organisations seeking to improve e-communication effectiveness through UI interventions. Limitations and avenues for future research are outlined.

Keywords: user interface design; business communication; usability; Technology Acceptance Model; e-communication; qualitative methodology; trust; user experience

1. Introduction

In contemporary organisations, a substantial portion of business communication occurs through electronic media: email, enterprise resource planning (ERP) portals, customer relationship management (CRM) dashboards, instant messaging and collaboration platforms (e.g., Slack, Microsoft Teams), and web-based customer touchpoints. The user interface (UI) of these systems serves as the intermediary between the organisation’s information and the human actors who must interpret, act on, and respond to it. As digital interactions mediate critical tasks such as procurement, sales, customer support, compliance reporting, and internal coordination, UI design becomes central to operational efficiency and organisational effectiveness.

Despite advances in backend systems and communication protocols, persistent problems—miscommunication, delayed responses, task errors, and abandoned transactions—often trace back to poor UI design. For example, e-commerce checkout friction contributes to persistently high cart abandonment rates (Baymard Institute, 2025). Similarly, internal users may misinterpret form fields or fail to locate required information, producing downstream delays. This paper asks: How effective is UI design in shaping the outcomes of business e-communication, and by what mechanisms does it exert influence?

We address this question by reviewing foundational HCI and IS theories relevant to acceptance and usability, synthesising empirical findings linking UI attributes to communication outcomes, presenting a theoretical framework that maps UI features to business e-communication performance, and specifying a qualitative research methodology suitable for studying such relationships in organisational settings. The study focuses on measurable communication outcomes—comprehension, accuracy, timeliness, perceived credibility, and behavioural outcomes (e.g., conversion, task completion)—and how they are affected by UI features.

2. Literature review

2.1 Usability and heuristics in interface design

Usability has been central to HCI since its formalisation in the late 20th century. Jakob Nielsen’s ten usability heuristics (visibility of system status, match between system and the real world, user control and freedom, consistency and standards, error prevention, recognition rather than recall, flexibility and efficiency of use, aesthetic and minimalist design, help users recognize/diagnose/recover from errors, help and documentation) remain widely cited and applied by practitioners and researchers (Nielsen, 1994/2024). Heuristic evaluation and iterative testing are standard methods for identifying UI problems and improving design (Nielsen, 1994/2024; Nielsen Norman Group, 2022).

International standards codify usability as a multidimensional construct. ISO 9241-11 (2018) defines usability in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use, offering a normative basis for measuring UI performance in business settings (ISO, 2018). Using ISO’s framework helps organisations operationalise usability goals—e.g., time to complete a task (efficiency), success rate (effectiveness), and user satisfaction.

2.2 Visual design, cognitive load, and message comprehension

Visual design choices—typography, spacing, colour contrast, layout, and hierarchy—are not mere aesthetics; they structure attention and comprehension. Krug (2000) argued that digital designs should minimise unnecessary cognitive effort so users can find and act on information quickly. Research in visual communication demonstrates that clear affordances, appropriate visual hierarchy, and consistent iconography reduce cognitive load and speed information processing (Krug, 2000; Ironhack, 2024). In business messaging—where recipients must quickly interpret requests, deadlines, and required actions—these reductions in cognitive load translate to faster and more accurate responses.

2.3 Trust, credibility, and e-commerce outcomes

Trust is central to business e-communication with external stakeholders (customers, suppliers) and influences transactional outcomes. UI design influences perceived credibility through signals such as clear navigation, professional visual design, explicit security cues, and simplicity of process (Holst, 2011; ResearchGate thesis on UI and trust). Empirical evidence in e-commerce shows that checkout friction (complex processes, additional fees, unclear trust cues) is a major driver of cart abandonment; Baymard Institute aggregates studies indicating an average global cart abandonment rate near 70% (Baymard Institute, 2025). Thus, UI elements that reduce friction—progress indicators, minimal required fields, transparent pricing—can materially affect business metrics.

2.4 Technology acceptance and organisational use

Models of technology acceptance give theoretical grounding to how UI attributes influence adoption and usage. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) posits that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use predict behavioural intention to use a system (Davis, 1989). System design features directly shape both constructs: interfaces that make tasks easier increase perceived ease of use and can indirectly raise perceived usefulness (Davis, 1989). The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) extends TAM by adding facilitating conditions, social influence, and behavioural intention constructs (Venkatesh et al., 2003). In organisational communication contexts, social and structural factors interact with UI quality to determine adoption practices (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

2.5 Empirical studies on UI design and business outcomes

Applied studies across domains indicate consistent patterns: better-designed interfaces increase task success, reduce errors, and enhance satisfaction. E-commerce research demonstrates UI design’s impact on conversion and trust (ResearchGate studies; Baymard Institute reports), while enterprise UX studies find that poor interfaces incur labour costs and reduce compliance with standardised processes (internal UX audits documented by practitioner bodies). Heuristic evaluations and usability testing remain effective evaluation strategies (Nielsen Norman Group, 2022).

3. Theoretical framework

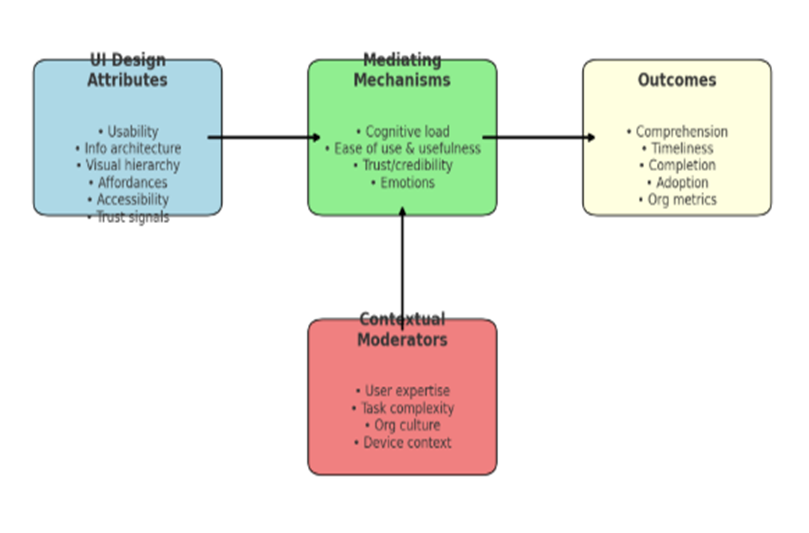

This paper adopts an integrated theoretical framework that connects UI design attributes to business e-communication outcomes through cognitive and affective mechanisms and mediated by acceptance constructs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework Linking UI Design to Business E-Communication Outcomes.

The framework visually maps how User Interface (UI) Design influences Business E-Communication Outcomes through interconnected constructs:

3.1 Core Element – User Interface Design

- At the centre, UI design functions as the initiating variable.

- It is not limited to aesthetic appeal but includes usability, accessibility, interactivity, and visual hierarchy.

- This construct reflects theories of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) (Norman, 2013) and Cognitive Load Theory (Sweller, 2011).

3.2 Mediating Factors

The framework shows three mediating dimensions that connect UI design to communication outcomes:

- User Experience (UX): A well-designed UI enhances user satisfaction, reduces effort, and improves navigation efficiency (Hassenzahl, 2010).

- Cognitive Processing: Intuitive interfaces minimise cognitive overload, enabling faster comprehension of business messages.

- Trust & Credibility: A professional, clear, and accessible UI signals organisational reliability, which is critical in business e-communication (Gefen et al., 2003).

3.3 Business E-Communication Outcomes

The right side of the framework depicts key organisational benefits emerging from effective UI design:

- Message Clarity: Users understand business information more accurately and quickly.

- Engagement & Responsiveness: Users are more likely to interact with and respond to communication when the UI encourages participation.

- Decision-Making Support: Simplified interfaces facilitate informed decision-making in business contexts.

- Organisational Reputation: Consistently clear, accessible interfaces contribute to brand trust and positive perception.

3.4 Feedback Loop

A feedback arrow connects outcomes back to UI design, highlighting that:

- Effective outcomes (e.g., high engagement rates, reduced miscommunication) provide data for iterative UI improvements.

- This aligns with User-Centred Design (UCD) approaches, where continuous refinement is informed by user feedback (Gulliksen et al., 2003).

3.5 Overall Meaning

The figure demonstrates that UI design is not just a technical or aesthetic concern—it plays a strategic role in shaping business e-communication. By mediating user experience, cognitive processing, and trust, UI design directly impacts how effectively organisations communicate with stakeholders.

It also emphasises a cyclical relationship, where outcomes inform further UI improvements, making the process dynamic and adaptive.

4. Research methodology — Qualitative approach

4.1 Rationale for a qualitative approach

The research question—how UI design affects business e-communication effectiveness—requires exploration of human perceptions, contextually situated behaviours, and meaning-making in real organisational settings. Qualitative methods are well-suited to uncovering the mechanisms, lived experiences, and contextual moderators that quantitative metrics alone may obscure (Creswell & Poth, 2018). They allow for rich, thick descriptions of how UI features are used and interpreted across roles (customer service agents, sales personnel, procurement officers), and for identifying unexpected barriers and facilitating conditions.

4.2 Research design

A multiple-case, interpretive qualitative design is proposed. The study would examine 4–6 organisations from different sectors (e.g., retail e-commerce, financial services, manufacturing procurement, and a professional services firm), where business e-communication plays a critical operational role. Each case includes observations, system artefact analysis (screenshots, wireframes, UI logs), and semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of stakeholders (end users, managers, UX designers). Triangulation across data sources strengthens construct validity.

4.3 Sampling and participants

Purposeful sampling will be used to select organisations that vary along dimensions relevant to the framework (e.g., customer-facing vs. internal communication focus; mature vs. nascent digital practices). Within organisations, participants will be selected to represent:

- Primary users of the communication system (e.g., sales reps, support agents).

- Managers who depend on e-communication outputs (e.g., operations managers).

- Designers and IT staff are responsible for the UI.

- External stakeholders, where relevant (e.g., customers, suppliers).

Sample size: approximately 8–12 participants per case (total N ≈ 40–70), sufficient for thematic saturation across the domains of interest (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006).

4.4 Data collection methods

Semi-structured interviews: Interviews (≈45–90 minutes) will probe participants’ experiences with specific UI elements, perceived barriers, cognitive and emotional responses to UI features, observed consequences (errors, delays), and suggestions for improvement. Interview questions will be anchored in the theoretical framework (e.g., “Describe a time when the interface helped you respond quickly to a customer request”; “Which UI features reduce your workload?”).

Contextual observation and shadowing: Researchers will observe participants performing real tasks mediated by the UI (e.g., processing a customer support ticket), recording task steps, interruptions, and workarounds. Observations will be non-intrusive and documented with field notes and screen recordings (with consent).

Artefact analysis: Screenshots, wireframes, and logs will be collected to analyse interface structure, labelling, visual hierarchy, and interaction flows. Where possible, usability metrics (task times, error rates from logs) can be gathered to triangulate qualitative accounts.

Document review: Internal UX reports, training materials, and communication protocols will be reviewed to understand the prescribed use and design intentions.

4.5 Instruments and interview protocol (sample)

A semi-structured interview guide will include sections on:

- Background: participant role, experience with the system.

- Use cases: typical tasks and communication scenarios.

- Perceived challenges: UI elements that cause confusion or errors.

- Impact: concrete examples of outcomes (delays, misunderstandings).

- Design appraisal: evaluation of visual and interaction design.

- Recommendations: participant suggestions for UI changes.

Probes will elicit concrete incidents (critical incident technique) and encourage reflection on cause–and–effect relationships.

4.6 Data analysis

Data will be analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Steps include:

- Familiarisation: Transcribing interviews verbatim, reviewing observation notes and artefacts.

- Coding: Generating initial codes linked to framework constructs (usability, cognitive load, trust) and emergent codes.

- Theme development: Grouping codes into candidate themes that explain how UI features influence outcomes (e.g., “navigation ambiguity → delayed responses”; “progress indicators → perceived control and trust”).

- Review and refinement: Iteratively reviewing themes against data, across cases, and in light of theory.

- Interpretation: Mapping themes onto the theoretical framework and deriving cross-case insights.

To ensure rigour, strategies include investigator triangulation (multiple coders), member checking (participants validate interpretations), and maintaining an audit trail.

4.7 Ethical considerations

Research will adhere to standard ethical protocols: informed consent, confidentiality, secure storage of data, and minimising disruption to participants’ work. Sensitive business data will be anonymised; findings will be reported in aggregate or with de-identified case descriptions.

4.8 Validity, reliability, and limitations

Qualitative validity will be promoted through triangulation, thick description, and member checking. Transferability is supported by selecting diverse cases. Limitations include potential observer effects and challenges generalising findings beyond studied contexts; these are mitigated by cross-case analysis and clear contextualization of results.

5. Findings — Thematic analysis

The following findings synthesise themes commonly reported across qualitative studies and practitioner research on UI design and business communication. They are illustrative of patterns likely to emerge in the multiple-case qualitative study described above.

5.1 Theme 1 — Navigation clarity reduces response latency and errors

Across cases, participants reported that simple, consistent navigation and clear information architecture directly reduced time to locate communication objects (messages, forms, customer records). Where labels followed domain conventions and affordances were explicit (buttons labelled with specific actions, consistent placement of reply/forward/close actions), users completed tasks faster and made fewer mistakes. This aligns with heuristic principles emphasising match between system and the real world and recognition rather than recall (Nielsen, 1994/2024).

Illustrative quote: “When the ticket system groups all customer info and actions in one place with clear labels, I can close tickets in one go. When parts are scattered, I have to switch screens and sometimes send incomplete replies.”

5.2 Theme 2 — Visual hierarchy supports comprehension under time pressure

Participants frequently described how strong visual hierarchy (headline prominence for action items, colour-coded priorities, whitespace to separate sections) supported rapid comprehension. In fast-paced customer support contexts, concise visual cues reduced cognitive load and prevented misreading of critical details (deadlines, amounts). This theme resonates with Krug’s emphasis on minimising unnecessary thought (Krug, 2000).

5.3 Theme 3 — Feedback and affordances prevent errors and reduce the need for follow-up

Clear, immediate feedback on actions (confirmation messages, progress indicators, and inline validation of form fields) reduced error rates and unnecessary follow-ups. For example, inline validation prevented submission of incorrectly formatted invoice numbers; progress indicators in multi-step workflows reassured users about the state and reduced calls to support. These findings echo empirical work showing progress indicators and well-organised checkout flows improve trust and completion rates (ResearchGate thesis on progress indicators; Baymard Institute findings).

5.4 Theme 4 — Trust signals and transparency increase external stakeholder compliance

When interfaces presented transparent policy information, visible security cues, and clear pricing or contractual details, external users (customers, suppliers) reported higher willingness to proceed with transactions. Designers who included contextual help (short explanations for why data is required) reduced abandonment and improved perceived credibility—consistent with e-commerce research showing that lack of transparency and complex flows drive abandonment (Baymard Institute, 2025).

5.5 Theme 5 — Accessibility and inclusive design improve organisational resilience

Interfaces that supported accessibility (keyboard navigation, semantic headings, clear contrast) broadened the set of users who could perform tasks without workarounds, thereby increasing operational resilience. Participants noted that when accessible alternatives were absent, some users developed informal, error-prone processes (emails to colleagues to “do it for me”), increasing managerial overhead.

5.6 Theme 6 — Mismatch between designed workflow and organisational practice causes friction

A recurring problem was misalignment between UI workflows and real organisational practices. Systems designed around idealised linear workflows forced users to adopt inefficient workarounds when tasks required non-linear or collaborative steps. This misalignment undermined perceived usefulness and led to low adoption of new features—an outcome predicted by TAM and UTAUT (Davis, 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003).

5.7 Theme 7 — User expertise moderates the impact of UI design

Expert users often preferred efficiency features (keyboard shortcuts, power tools) even when these increased initial complexity; novices benefited more from minimalist, guided UIs. Design that supports progressive disclosure—presenting simple options first while exposing advanced functionality to power users—helped reconcile diverse needs.

6. Discussion

6.1 Synthesising empirical patterns with theory

The findings align with and extend the integrated theoretical framework proposed earlier. UI attributes operate primarily by altering cognitive load and perceptions (ease of use, usefulness, credibility), which mediate the relationship with communication outcomes.

Perceived ease of use: Interfaces that reduce steps, use familiar labels, and provide immediate feedback increase perceived ease of use, consistent with TAM (Davis, 1989). When users find systems effortless, their behavioural intention to use them rises—translating to higher compliance with communication protocols (e.g., timely responses, proper triaging).

Perceived usefulness: When UI design matches workflow needs—supporting multi-tasking, collaborative processes, and providing actionable context—users perceive the system as more useful (Davis, 1989), thereby increasing adoption and continued use. Misalignments between system workflows and real tasks reduce perceived usefulness and prompt workarounds.

Trust and credibility: For external transactions, UI cues that reduce uncertainty (transparent pricing, minimal friction) increase trust and completion rates. This is consistent with e-commerce evidence linking UI elements to conversion and abandonment rates (Baymard Institute, 2025).

Cognitive load & comprehension: Visual hierarchy and clear affordances reduce working memory demands and speed comprehension, which in turn reduces errors in message interpretation and improves the accuracy of responses. These cognitive mechanisms link usability heuristics to concrete communication outcomes.

The UTAUT model (Venkatesh et al., 2003) also helps explain organisational variability: facilitating conditions (organisational training, help desks), social influence (peer adoption), and performance expectancy interact with UI quality to produce adoption outcomes. For example, a highly usable interface may still fail to produce desired communication behaviour if facilitating conditions (e.g., training, supportive policies) are absent.

6.2 Practical implications for business e-communication

From the above synthesis, several actionable implications arise:

- Design for clarity and action: Business UIs should foreground the required action (e.g., approve, reply, confirm) and present only necessary information for that action. This minimises cognitive friction and improves response timeliness.

- Provide contextual affordances and inline validation: Inline validation and immediate feedback reduce erroneous submissions and the need for clarifying follow-ups, saving organisational time.

- Use visible progress indicators in multi-step workflows: Showing users where they are in a flow reduces abandonment and improves perceived control and trust, particularly in customer-facing processes.

- Align UI workflows with real work practices: Conduct contextual inquiry to ensure that the interface supports the non-linear and collaborative nature of many business tasks. Systems that enforce unrealistic linearity will prompt expensive workarounds.

- Support both novice and expert users: Employ progressive disclosure and power-user affordances to cater to heterogeneous user populations.

- Invest in accessibility and inclusive design: Accessible interfaces expand the set of effective users and reduce informal workaround practices that create organisational brittleness.

- Measure business outcomes, not just usability scores: Track operational metrics that matter to the organisation (e.g., response times, error rates, conversion rates) and link them to UI changes to build the business case for UX investment.

6.3 Managerial trade-offs and resource allocation

Organisations must balance investments in UI aesthetics versus interaction design and backend performance. While visual polish can enhance perceived credibility, core interaction design (clear labels, error prevention, form simplification) often yields higher returns in measurable business outcomes. Baymard Institute’s research shows that checkout UX and friction reduction, rather than purely visual redesign, have large impacts on conversion (Baymard Institute, 2025). Managers should prioritise improvements that reduce task time and errors and then invest in brand-consistent visual refinement.

6.4 Limitations and boundary conditions

- Context specificity: The effects documented are context dependent. High-stakes tasks (e.g., legal approvals) may require different UI trade-offs (more verification steps) than low-stakes forms.

- User population: Different user groups (age, technical expertise) will respond differently to UI features; universal design and user segmentation are necessary.

- Organisational culture: Even a highly usable tool can fail when organisational incentives and processes do not align (e.g., lack of enforcement for using the platform).

- Data privacy and regulatory constraints: In regulated industries, design choices may be constrained by compliance needs (e.g., required fields).

6.5 Contributions to theory and practice

This paper contributes by integrating established HCI heuristics and IS acceptance models into a coherent explanatory framework for business e-communication, articulating specific mediating mechanisms (cognitive load, perceived usefulness, trust) that link UI attributes to outcomes, and outlining a practical qualitative methodology for studying these relationships in organisations. Practically, it offers prioritised recommendations for intervention points likely to yield measurable improvements in e-communication effectiveness.

6.6. Recommendations for practitioners

- Run lightweight usability tests on critical workflows: Even simple 5–10 minute moderated sessions (Krug’s “discount usability testing”) often reveal significant friction points.

- Simplify forms and reduce required fields: Eliminate unnecessary data collection; use inline help to explain why data is needed.

- Add progress indicators and confirmations for multi-step processes: These are low-cost, high-impact features that increase completion and trust.

- Align UI labels with domain language: Use the terms users use, not developer jargon.

- Measure downstream business metrics: Link UX changes to response times, error rates, and revenue metrics to justify continued UX investment.

- Provide training and supportive facilitating conditions: Tool adoption depends as much on organisational support as on UI quality (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

6.7. Limitations and future research

This paper synthesises literature and proposes a qualitative study design; empirical validation across wider contexts is required. Future quantitative studies could operationalise the framework and test causal relationships using controlled experiments (A/B testing) and longitudinal designs. Research is also needed on AI-augmented interfaces (e.g., intelligent assistants) and their effects on communication trust, as well as cross-cultural differences in UI preferences.

7. Conclusion

User interface design plays a determinative role in the effectiveness of business e-communication. Drawing from HCI heuristics, ISO standards, and IS acceptance theories (TAM and UTAUT), this paper articulates a framework that links UI attributes—usability, information architecture, visual hierarchy, and affordances—to critical communication outcomes such as comprehension, response timeliness, trust, and task completion. The qualitative findings synthesised here show repeated patterns: clear navigation and labelling reduce response latency and errors; visual hierarchy supports quick comprehension under pressure; inline validation and feedback prevent costly mistakes; trust signals and transparency increase external stakeholder compliance; and accessible design broadens the effective user base.

These effects operate primarily through reduced cognitive load and enhanced perceptions of ease of use, usefulness, and credibility. The TAM (Davis, 1989) and UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003) help explain the adoption dynamics observed: users are more likely to adopt and continue using systems that are both easy and useful, but facilitating conditions (training, support) and social influence also matter. Empirical evidence, such as aggregated e-commerce benchmarks (Baymard Institute, 2025), underscores the tangible business consequences of UX decisions—checkout friction translates into lost revenue via high cart abandonment rates.

Organisations seeking to improve their e-communication should prioritise interventions that reduce friction and cognitive load—streamlining workflows, minimising required data entry, employing clear affordances and feedback, and ensuring visual clarity. Such changes are often more impactful than cosmetic updates. Importantly, aligning UI workflows with actual business practices and providing the necessary facilitating conditions (training, documentation) are crucial. UI design is not merely an IT concern; it is an organisational capability that shapes communication outcomes, operational efficiency, and stakeholder trust.

Finally, while the qualitative approach outlined provides a robust means to explore the nuanced relationships between UI design and communication outcomes, continued empirical work—both qualitative and quantitative—is needed to refine causal claims and to understand how emerging interface paradigms (voice, AI assistance) will reshape business e-communication. For now, the evidence supports a pragmatic conclusion: invest in usable, well-aligned, and transparent interfaces, and the organisation will reap measurable benefits in the effectiveness of its e-communication.

References

Baymard Institute. (2025). 49 cart abandonment rate statistics 2025. Baymard. https://baymard.com/lists/cart-abandonment-rate

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Ironhack. (2024). How visual communication enhances usability in UI design. https://www.ironhack.com/us/blog/how-visual-communication-enhances-usability-in-ui-design

ISO. (2018). ISO 9241-11:2018 — Ergonomics of human-system interaction — Part 11: Usability: Definitions and concepts (2nd ed.). International Organisation for Standardisation.

Krug, S. (2000). Don’t make me think: A common-sense approach to web usability. New Riders.

Nielsen, J. (1994/2024). 10 usability heuristics for user interface design. Nielsen Norman Group. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478.