Journal Home Page

OPEN ACCESS

Time Management Strategies for Graphic Design Students: Bridging Creativity and Productivity

| Anik Chandra Das ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0054-9540 Shafiul Alom ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3357-026X Md. Yahya Tazvir ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-8266-0271 Kaiom Sheikh ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8248-7102 Md. Rafiul Islam Rafi ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7076-1157 Omar Huzaifa ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0004-0665-7780 Momtahina Binta Aziz ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-6412-9188 Department of Graphic Design & Multimedia Faculty of Design & Technology Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh |

| Prof. Dr Kazi Abdul Mannan Department of Business Administration Faculty of Business Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: drkaziabdulmannan@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-132X Corresponding author: Anik Chandra Das: smuct.anik@gmail.com |

Learn. polic. strategies. 2026, 5(1); https://doi.org/10.64907/xkmf.v5i1.lps.1

Submission received: 2 October 2025 / Revised: 8 November 2025 / Accepted: 16 December 2025 / Published: 2 January 2026

Abstract

This article investigates time management strategies that support both creativity and productivity among undergraduate graphic design students. Using a qualitative research design grounded in phenomenology and thematic analysis, semi-structured interviews were conducted with eighteen students enrolled in bachelor-level graphic design programs across three universities. Findings reveal five major themes: rhythmic scheduling and flow facilitation, task segmentation and milestone mapping, environment and tool affordances, boundary-setting and wellbeing practices, and reflective practice and portfolio-oriented prioritisation. The study highlights tensions between open-ended creative work and structured productivity techniques, and proposes an integrated framework—Creative-Time Integration (CTI)—that synthesises cognitive-affective, behavioural, and contextual strategies. Practical recommendations for educators and students include curriculum-integrated time literacy training, scaffolded project milestones, studio-designated uninterrupted work periods, and reflective journaling. The article contributes to design education literature by offering empirically grounded, actionable strategies that respect creative processes while enhancing timely project completion.

Keywords: time management, graphic design education, creativity, productivity, qualitative research, thematic analysis

1. Introduction

Time is a critical resource for students in higher education. For graphic design students—whose workflows interweave ideation, iterative prototyping, critique cycles, and technical execution—time management is not merely an efficiency problem but an epistemic and pedagogical challenge. Balancing the open-ended demands of creativity with deadlines and assessment requirements requires strategies that preserve creative freedom while ensuring consistent progress (Amabile, 1996; Cross, 2006). Despite widespread attention to time management in general student populations (Macan, 1994; Claessens, van Eerde, Rutte, & Roe, 2007), there is a relative paucity of research that directly addresses the specific needs of creative disciplines where unstructured exploration and flow states are central to learning outcomes.

This article explores how graphic design students manage time, the tensions they face between creativity and productivity, and practical strategies that mediate these tensions. We employ a qualitative approach to capture the lived experiences, perceptions, and tacit knowledge of students. The research aims to inform pedagogical interventions and studio practices that foster both creative development and timely project completion.

1.1 Rationale and significance

Design educators frequently report that students struggle to manage project timelines, often leaving substantial work until shortly before deadlines (Lawson, 2006). Such practices can reduce the opportunity for reflection and iterative refinement, negatively affecting learning and the quality of outcomes. Moreover, poor time management can exacerbate stress and reduce well-being, which, paradoxically, impedes creative performance (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). By focusing on the intersection of creativity and time management, this study aims to produce strategies that are sensitive to the unique cognitive and affective processes of design practice.

1.2 Research questions

This study addresses the following research questions:

- How do graphic design students experience and perceive time when engaged in creative project work?

- What time management strategies do they adopt to balance creativity and productivity?

- What barriers and facilitators influence effective time use in studio-based learning?

- How can educators support time practices that preserve creativity while improving timely completion and reflective learning?

2. Literature Review

2.1 Time management and students

Time management has long been recognised as a predictor of academic performance. Macan (1994) conceptualised time management as a multidimensional construct including attitudes toward time, planning behaviour, and perceived control. Meta-analytic and review studies show modest positive relationships between time management and academic outcomes (Claessens et al., 2007). Traditional time management interventions—goal-setting, prioritisation, scheduling—are effective for routine, linear tasks but may be perceived as constraining by creative practitioners.

2.2 Creativity and workflow in design education

Creativity in design is characterised by iterative cycles of divergent and convergent thinking, frequent prototyping, and critical reflection (Amabile, 1996; Cross, 2006). Flow experiences—periods of deep immersion and optimal engagement—are widely reported by creative professionals and students alike (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). However, flow is sensitive to perceived time pressure; both excessive deadlines and chaotic scheduling can interrupt deep work (Newport, 2016).

2.3 Time management models relevant to creative work

Several theoretical approaches offer insights. The self-regulated learning (SRL) framework highlights planning, monitoring, and reflection as core components of effective academic work (Zimmerman, 2002). For creative cognition, models emphasise a balance between structured constraints and exploratory freedom (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999). Task segmentation theories recommend breaking complex tasks into manageable subtasks to reduce cognitive load and procrastination (Steel, 2007). Lastly, the dual-process view suggests that creative ideation (Type 1 processes) and evaluative judgment (Type 2 processes) require different temporal affordances (Kahneman, 2011).

2.4 Time management tools and techniques

Popular time techniques include Pomodoro (Cirillo, 2006), time blocking, and priority matrices. Digital task managers and calendar integrations have become common (Giannakos et al., 2018). Research on creative professionals suggests that tool adoption is successful when tools are flexible and support intermittent deep work rather than rigid templates (Perlow, 1999). Pedagogical studies emphasise that time management must be taught as a craft—a reflective and contextual practice—rather than only as a set of rules (Barkley, Cross, & Major, 2005).

2.5 Gap in the literature

There is limited empirical work examining how time management strategies interact with creative processes in design education. Studies often treat creativity and time management separately or rely on quantitative measures that do not capture the lived experience of students. This study aims to fill the gap using qualitative methods to generate theory and practice-relevant recommendations.

3. Theoretical Framework

This study is guided by an integrated theoretical framework—the Creative-Time Integration (CTI) framework—developed from a synthesis of self-regulated learning (Zimmerman, 2002), creative cognition (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999), flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996), and time-management behaviour models (Macan, 1994). The CTI framework posits that effective time management for creative students emerges from alignment among three core domains:

- Cognitive-Affective Processes: Includes ideation patterns, attention regulation, mood influences, and flow states. These determine when and how students can perform deep creative work.

- Behavioural Strategies: Concrete actions such as planning, scheduling, task segmentation, prioritisation, and tool use (e.g., Pomodoro, time blocking).

- Contextual Affordances: Environmental and institutional factors, including studio layout, access to resources, tutor feedback timing, and assessment structures.

Under CTI, student success in managing time is a function of dynamic interactions among these domains. For instance, behavioural strategies (e.g., scheduled deep-work sessions) must be aligned with cognitive-affective readiness (e.g., times of day when the student can enter flow) and contextual affordances (e.g., availability of a quiet studio). The framework also includes metacognitive reflection—students’ ongoing monitoring and adaptation of strategies—as a mediating mechanism.

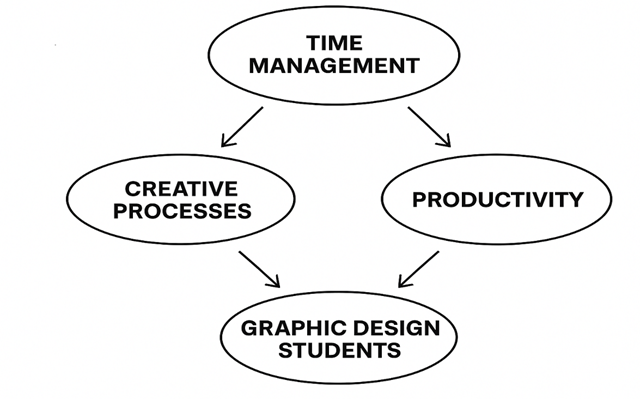

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework of Creative-Time Integration (CTI)

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework linking time management, creativity, productivity, and graphic design students. At the top, time management acts as the central driver, influencing both creative processes and productivity. Effective time strategies allow students to allocate sufficient uninterrupted periods for ideation and exploration while maintaining progress toward deadlines. On the left, creative processes benefit from protected time blocks that nurture divergent thinking, experimentation, and flow states. On the right, productivity emerges from structured scheduling, prioritisation, and milestone mapping. Both creativity and productivity converge toward the experience of graphic design students, who must balance these dual demands in their academic practice. The framework highlights that time management is not simply about efficiency, but about harmonising structured productivity with the flexibility necessary for creativity. Ultimately, the model positions time as a mediating factor that shapes both student well-being and the quality of design outcomes.

4. Research Methodology

4.1 Research design

A qualitative phenomenological design was selected to explore the lived experiences of graphic design students regarding time and creativity. Phenomenology is appropriate when seeking deep, nuanced understandings of participants’ subjective experiences (Creswell, 2013). Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and complemented by reflective logs supplied by participants.

4.2 Participants and sampling

Eighteen undergraduate graphic design students were recruited via purposive sampling from three universities with accredited design programs. The sample included students across years 2 to 4 to capture varied levels of studio experience. Participant demographics: 12 female, 6 male; ages ranged from 19 to 24. Ethical approval was obtained from the lead researcher’s institutional review board; informed consent and anonymisation procedures were followed.

4.3 Data collection

Data collection occurred over eight weeks. Each participant completed a brief demographic questionnaire, a two-week reflective log (documenting time use, perceived productivity, and creative states), and a 45–60 minute semi-structured interview. Interview topics covered time perceptions, strategies used, challenges faced, impact of studio culture, and recommendations for educational support.

4.4 Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis approach. Thematic analysis allows for systematic identification of patterns across data while remaining flexible to context. Initial coding was inductive, followed by iterative refinement into higher-order themes. Reflective logs were used for triangulation and to validate interview themes.

4.5 Trustworthiness

To ensure credibility and trustworthiness, the study used multiple strategies: member checking (participants reviewed emergent theme summaries), peer debriefing with design faculty, and maintaining an audit trail of analytic decisions (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Reflexive journaling by the researcher addressed potential biases.

4.6 Limitations

As with most qualitative research, findings are contextually situated and not statistically generalizable. The purposive sample from three institutions provides depth but may not capture the full diversity of design education contexts globally. Future research could combine these qualitative insights with larger-scale quantitative validation.

5. Findings

Analysis produced five major themes that collectively describe how graphic design students manage time to balance creativity and productivity: rhythmic scheduling and flow facilitation, task segmentation and milestone mapping, environment and tool affordances, boundary-setting and wellbeing practices, and reflective practice and portfolio-oriented prioritisation.

5.1 Rhythmic scheduling and flow facilitation

Participants frequently described the importance of matching work types to personal energy cycles. Several students reported that ideation often occurred in the evening or late at night, while execution and technical work were scheduled for mornings when attention to detail was closer. One participant explained:

“I sketch and brainstorm at night when ideas come, but I do precise layout work in the morning because I’m less sleepy and steadier.”

Interview data indicated that students recognised flow states as crucial for breakthrough ideas and actively sought to protect extended, uninterrupted periods for such work. However, pervasive studio interruptions and concurrent coursework sometimes fragmented these opportunities.

Students used informal heuristics—“two-hour deep blocks” or “long weekend sprints”—to deliberately induce flow. While some used Pomodoro-style breaks to maintain momentum, others felt short intervals were too disruptive for deep ideation.

5.2 Task segmentation and milestone mapping

Breaking large projects into discrete subtasks emerged as a widely adopted strategy. Students described creating milestone maps that aligned with assessment rubrics: research, concept generation, prototyping, critique preparation, and finalisation. This segmentation served both cognitive and motivational functions: it reduced overwhelm and provided frequent points of feedback.

Notably, participants emphasised the need to schedule critique rehearsal and buffer time for unexpected technical problems (e.g., printing failures). Several students used backward planning from deadlines to allocate time for each milestone, a practice aligned with goal-setting theory and backward design principles.

5.3 Environment and tool affordances

Physical and digital environments shaped time use. Studio spaces that allowed for flexible furniture arrangements, portable workstations, and zones for quiet work supported longer deep-work sessions. Conversely, crowded or noisy studios pushed students to retreat to home setups or libraries.

Tool affordances—version control, cloud storage, and simple task managers—were cited as enabling faster iteration and less rework. Participants who maintained tidy file systems and naming conventions reported fewer time losses. Digital distractions (social media, notifications) were a recurrent challenge; students used app blockers and “do not disturb” modes selectively.

5.4 Boundary-setting and well-being practices

Time management was frequently framed as boundary work: protecting creative time from encroaching tasks and maintaining well-being to sustain creativity. Sleep, exercise, and social time were acknowledged as foundational to sustained creativity. Several students highlighted that overwork led to diminishing creative returns: after long stretches of late-night work, ideation and judgment quality declined.

Boundary-setting practices included explicit rules such as “no deadlines on the same week as midterms” (where possible), calendar-based blocks labelled as “studio focus,” and negotiated timelines with teammates in group projects. Those who reported better time practices often had norms established within their peer groups or studio culture that respected individual work rhythms.

5.5 Reflective practice and portfolio-oriented prioritisation

Students who engaged in regular reflection—through sketchbooks, process journals, or weekly reviews—reported greater clarity about what tasks required focused effort and which could be deferred. Reflection promoted prioritisation based on long-term portfolio goals rather than short-term task urgency. For example, participants prioritised projects that demonstrated techniques they wanted in their portfolios, allocating more time to such projects early on.

Reflection also supported adaptive strategy changes; students iteratively refined their schedules after noticing consistent bottlenecks (e.g., printing delays, software learning curves).

6. Discussion

6.1 Interpreting the themes through CTI

The five themes map directly onto the CTI framework. Rhythmic scheduling corresponds to cognitive-affective alignment (matching tasks to energy and flow). Task segmentation and milestone mapping are behavioural strategies that scaffold the creative process. Environment and tool affordances are contextual factors that either enable or constrain productive creative work. Boundary-setting and wellbeing practices highlight the role of affective regulation and social norms, while reflective practice functions as metacognitive monitoring—central to CTI’s adaptive loop.

6.2 Tensions between structure and freedom

A central tension was how students reconcile the need for open, explorative time with the regimented structures of academic deadlines. Some students experienced prescriptive time techniques (e.g., strict Pomodoro cycles) as antithetical to creativity, while others adapted such techniques selectively—using longer blocks for ideation and shorter cycles for technical tasks. This suggests that rigid time prescriptions are less effective than flexible, context-sensitive strategies that allow students to modulate structure according to task demands (Sternberg & Lubart, 1999; Newport, 2016).

6.3 Pedagogical implications

Findings suggest several pedagogical interventions:

Integrate time literacy into curricula: Teach students about chronotypes, flow, task segmentation, and backward planning. Time literacy should be treated as a design skill rather than a remedial study habit. Short workshops and embedded assignments can scaffold these competencies (Barkley et al., 2005).

Scaffold milestones and formative checkpoints: Instead of single, high-stakes deadlines, use staged submissions that align with natural creative phases: research, concept sketches, prototype, critique, and final. This reduces last-minute rushes and supports iteration (Cross, 2006).

Designate studio deep-work windows: Encourage institutional norms that protect uninterrupted studio time—e.g., two-hour “studio focus” blocks—while balancing access and critique needs.

Teach reflective practices: Process journals, project retrospectives, and portfolio mapping can help students prioritise work that aligns with long-term goals and refine time strategies.

Promote technical ‘time-savers’: Provide workshops on efficient file management, print workflows, and basic scripting/macros where relevant. Reducing technical friction frees time for creative exploration.

6.4 Mental health and sustainable productivity

The study reinforces that sustainable creativity requires attention to well-being. Educators should avoid excessive workload clustering and promote policies that discourage chronic all-nighters. Peer norms and supportive feedback structures are crucial in establishing sustainable studio cultures (Lawson, 2006).

6.5 Contributions to theory and practice

This study contributes an empirically grounded CTI framework that explicates how cognitive, behavioural, and contextual factors interact to shape time management in creative education. Practically, it identifies specific, student-validated strategies—rhythmic scheduling, milestone mapping, environment design, boundary-setting, and reflective journaling—that educators can integrate into curricula and studio policies.

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

This research sought to understand how graphic design students manage time when balancing creativity and productivity. Through qualitative inquiry, the study identified five interrelated strategies and proposed the Creative-Time Integration framework that emphasises the interplay among cognitive-affective processes, behavioural strategies, and contextual affordances. Key recommendations include integrating time literacy into design curricula, scaffolding project milestones to enable iterative work, protecting deep-work studio windows, teaching practical technical workflows, and embedding reflective practices to support adaptive time strategies.

Educators should approach time management as a design problem—one that requires iterative experimentation, contextual sensitivity, and student agency. By reframing time as an element of design practice rather than a mere administrative constraint, design programs can foster healthier, more productive creative learning environments.

7.1 Practical checklist for educators

- Introduce a short module on time literacy (chronotypes, flow, segmentation).

- Use staged deadlines with formative feedback at each milestone.

- Implement optional “deep-work” studio hours weekly.

- Offer workshops on file/print workflow efficiency.

- Require or encourage reflective logs tied to portfolio development.

7.2 Suggestions for future research

Future studies could test CTI-informed interventions using mixed methods and experimental designs to quantify impacts on learning outcomes, creativity measures, and well-being. Research could also investigate cultural and institutional variations in studio norms and the role of remote/hybrid studio models on time practices.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to ‘The social psychology of creativity’. Westview Press.

Barkley, E. F., Cross, K. P., & Major, C. H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Bennett, A. (2012). Studio culture and student time: Rethinking deadlines. Journal of Design Education, 35(1), 22–39.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Bryson, J. M. (2018). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organisations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organisational achievement (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Claessens, B. J. C., van Eerde, W., Rutte, C. G., & Roe, R. A. (2007). A review of the time management literature. Personnel Review, 36(2), 255–276.

Cirillo, F. (2006). The Pomodoro Technique. (Self-published).

Cross, N. (2006). Designerly ways of knowing. Springer.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. HarperPerennial.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Giannakos, M. N., Jaccheri, L., & Mylonas, P. (2018). Time management tools and learning: A review. Education and Information Technologies, 23(6), 2567–2590.

Grant, R. M. (2016). Contemporary strategy analysis (9th ed.). Wiley.

Hastings, G. (2016). Social marketing: Why should the devil have all the best tunes? Routledge.

Hrebiniak, L. G. (2005). Making strategy work: Leading effective execution and change. Wharton School Publishing.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilisation of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler & E. Katz (Eds.), The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19–32). Sage.

Kitchen, P. J., & Burgmann, I. (2015). Integrated marketing communications: Making it work at a strategic level. Journal of Business Strategy, 36(4), 34–39.

Kliatchko, J. (2008). Revisiting the IMC construct: A revised definition and four pillars. International Journal of Advertising, 27(1), 133–160.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Lawson, B. (2006). How designers think: The design process demystified (4th ed.). Architectural Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Macan, T. H. (1994). Time management: Test of a process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(3), 381–391.

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72(1), 107–114.

Newport, C. (2016). Deep work: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. Grand Central Publishing.

Perlow, L. A. (1999). The time famine: Toward a sociology of work time. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 57–81.

Rust, R. T., Ambler, T., Carpenter, G. S., Kumar, V., & Srivastava, R. K. (2004). Measuring marketing productivity: Current knowledge and future directions. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 76–89.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1999). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3–15). Cambridge University Press.

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94.

Tiago, M. T. P. M. B., & Veríssimo, J. M. C. (2014). Digital marketing and social media: Why bother? Business Horizons, 57(6), 703–708.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.