Journal Home Page

OPEN ACCESS

Leadership Styles and Team Collaboration in Multimedia Production Projects

| Mansura Aktar ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3454-8356 Abu Sayem ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-8784-3459 Zannatul Zahra Chowdhury ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-1857-5210 Yeasin Rifat ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0459-0284 Md Yeasin Arafat ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0005-2348-4647 Sadika ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-5067-278X Department of Graphic Design & Multimedia Faculty of Design & Technology Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh |

| Prof. Dr Kazi Abdul Mannan Department of Business Administration Faculty of Business Shanto-Mariam University of Creative Technology Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: drkaziabdulmannan@gmail.com ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-132X Corresponding author: Mansura Aktar: mansooraaktar00@gmail.com |

Percept. motiv. attitude stud. 2026, 5(1); https://doi.org/10.64907/xkmf.v5i1.pmas.1

Submission received: 3 November 2025 / Revised: 9 December 2025 / Accepted: 17 December 2025 / Published: 2 January 2026

Download (PDF) (594 KB)

Abstract

Multimedia production projects—characterised by interdisciplinary teams, tight deadlines, iterative creative processes, and complex technical workflows—place distinct demands on leadership and team collaboration. This study investigates how different leadership styles influence collaboration, creativity, coordination, and project outcomes in multimedia production environments. Drawing on transformational, transactional, situational, and distributed leadership theories and integrating models of team development and creativity, the research employs a qualitative, multiple-case study design. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 22 multimedia practitioners (producers, directors, designers, developers, and project managers), participant observation of three production teams, and document analysis of project artefacts. Thematic analysis revealed four major themes: (1) adaptive leadership fosters creative risk-taking and psychological safety; (2) directive leadership supports technical coordination under tight constraints; (3) distributed leadership and clear role complementarity increase resilience; and (4) communication practices and shared mental models mediate the relationship between leadership style and collaboration quality. Practical implications for media managers, creative directors, and educators are discussed, and recommendations are offered for aligning leadership approach with project stage, team composition, and organisational culture.

Keywords: leadership styles, team collaboration, multimedia production, creativity, distributed leadership, qualitative research

1. Introduction

Multimedia production projects—ranging from short films, interactive installations, and advertising campaigns to game cutscenes and educational media—require the coordinated effort of professionals from diverse disciplines (e.g., visual design, audio engineering, programming, storytelling, animation). This interdisciplinary collaboration makes leadership a critical determinant of project success. Leadership is not merely about issuing commands or managing schedules; it shapes creative climates, mediates conflict, and forms the scaffolding within which collaboration, innovation, and technical coordination occur (Bass, 1985; Goleman, 2000). Yet the distinctive hybrid nature of multimedia work—combining artistic uncertainty and technical complexity—means that leadership demands differ from those in more routine production settings (Amabile, 1996; Sawyer, 2007).

This article explores how different leadership styles affect team collaboration in multimedia production projects. By focusing on the lived experiences of practitioners and analysing how leadership practices unfold in real-world projects, the study seeks to produce actionable insights for practitioners and contribute to theoretical understanding at the intersection of leadership studies and creative team research.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Leadership Styles and Creative Work

Leadership literature distinguishes several archetypal styles: transformational, transactional, situational, and distributed leadership. Transformational leadership—characterised by vision, intellectual stimulation, and individualised consideration—has been linked with increased motivation and innovation in teams (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transactional leadership emphasises contingent rewards and task monitoring and is often effective in environments where clarity and adherence to technical specifications are crucial (Burns, 1978; Yukl, 2013). Situational leadership posits that leaders must adapt their style to the maturity and needs of followers and to task demands (Hersey & Blanchard, 1969). Distributed or shared leadership recognises leadership as a collective process distributed across members and artefacts rather than located in a single individual (Gronn, 2002; Spillane, 2006).

In creative industries, transformational leadership is frequently lauded for fostering intrinsic motivation and creative output (Amabile, 1996; Mumford et al., 2002). However, purely transformational approaches may neglect the coordination and technical oversight required in complex multimedia projects (Keller, 2016). Scholars therefore suggest a contingent view: the efficacy of leadership styles depends on project characteristics, team composition, and organisational context (Zhu et al., 2018).

2.2 Team Collaboration in Multimedia Environments

Collaboration in multimedia production involves both cognitive and sociotechnical coordination—shared mental models about the project, negotiation of creative decisions, and synchronisation of temporal workflows (Tushman & Nadler, 1978; Salas et al., 2008). Models of team development, such as Tuckman’s (1965) forming–storming–norming–performing framework, help explain how teams evolve, but creative teams also require mechanisms for idea convergence and divergence (Sawyer, 2007).

Psychological safety—a climate where members feel safe to take interpersonal risks—is crucial for creativity and knowledge sharing in teams (Edmondson, 1999). Leadership plays a decisive role in establishing psychological safety through behaviours that encourage voice, model vulnerability, and respond constructively to failure (Edmondson, 1999; Detert & Burris, 2007).

2.3 Leadership, Communication, and Tools

Digital collaboration tools, pipelines (e.g., version control, asset management), and standardised review processes (dailies, playtests, sprint demos) mediate how leadership choices affect coordination (Rigby et al., 2016). Leaders who combine clear processes with open communication channels help teams manage dependencies and maintain creative momentum (Hackman, 2002). Several studies indicate that different leadership approaches interact with tools: for example, a distributed leadership culture aligns well with collaborative platforms and iterative workflows (Avolio et al., 2009).

3. Theoretical Framework

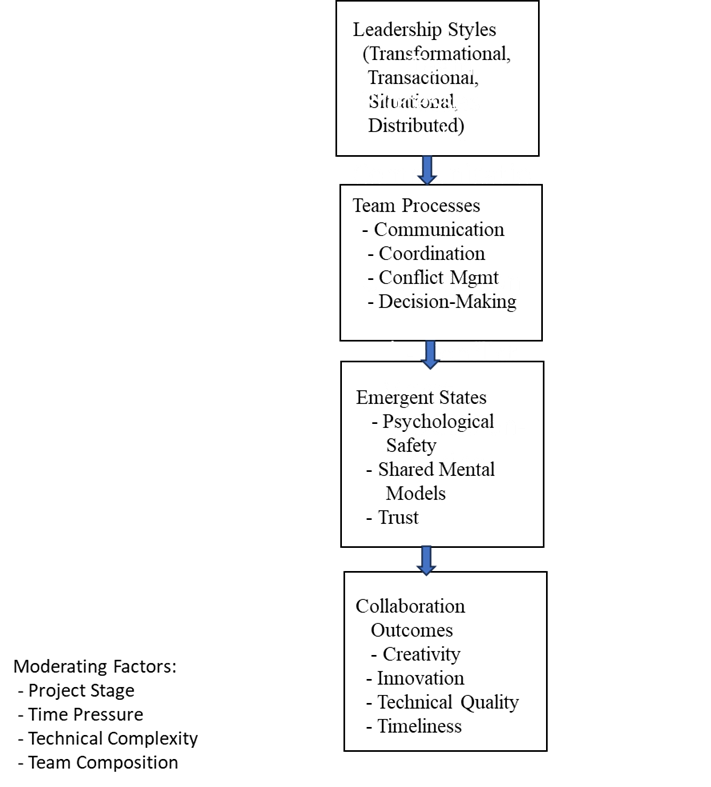

This study draws on a combined theoretical framework integrating leadership theories with models of team creativity and development. The framework consists of three interlocking components:

Leadership Styles Spectrum: Following Bass (1985) and Goleman (2000), leadership styles are categorised into transformational, transactional, situational (adaptive), and distributed/shared leadership. Each style is expected to produce different relational and task outcomes in multimedia settings.

Team Processes and States: Based on Hackman (2002) and Salas et al. (2008), the framework posits that leadership influences team processes (communication, coordination, conflict management) and emergent states (psychological safety, shared mental models), which in turn shape collaboration quality and creative outcomes.

Project Contextual Factors: Drawing from contingency thinking (Fiedler, 1967), project factors (time pressure, technical complexity, team heterogeneity, stage of production) moderate the relationship between leadership style and collaboration outcomes.

The conceptual model (Figure 1) positions leadership style as the independent variable, mediated by team processes and emergent states, producing dependent variables such as collaboration quality, creativity, technical quality, and timeliness; contextual moderators influence path strengths.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model: Leadership Styles and Team Collaboration in Multimedia Production

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework guiding this study. Leadership styles—transformational, transactional, situational, and distributed—are positioned as the independent variable influencing team functioning in multimedia production projects. These leadership styles shape team processes such as communication, coordination, conflict management, and decision-making. Effective team processes foster emergent states, including psychological safety, shared mental models, and interpersonal trust, which are critical for sustaining collaboration under creative and technical pressures. In turn, these emergent states determine collaboration outcomes, such as enhanced creativity, innovation, technical quality, and timeliness of project delivery. The model also incorporates contextual moderators—project stage, time pressure, technical complexity, and team composition—that condition the strength and direction of leadership effects. Thus, the model emphasises that leadership in multimedia production is not static but contingent, requiring adaptive, distributed, and context-sensitive approaches to enable optimal team collaboration and project success.

3.1. Research Questions

The study addresses the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: How do different leadership styles manifest in multimedia production projects?

- RQ2: In what ways do leadership styles influence team collaboration, communication, and creativity?

- RQ3: What contextual factors moderate the effectiveness of particular leadership styles in multimedia projects?

- RQ4: What practical leadership practices support optimal collaboration in multimedia production environments?

4. Research Methodology

4.1 Research Design

A qualitative, multiple-case study approach was selected to capture rich, contextualised understandings of leadership practices across different multimedia production settings (Yin, 2018). Qualitative methods are appropriate for exploring processes, meanings, and complex social interactions that are not readily quantifiable (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Creswell & Poth, 2018).

4.2 Site and Participant Selection

Three multimedia production organisations were purposefully sampled to provide variation in project type and organisational scale: (A) an independent short-film collective; (B) a mid-size digital agency producing interactive campaigns and motion graphics; and (C) a small game studio creating episodic narrative experiences. Within these sites, 22 participants were recruited using purposive and snowball sampling to include a range of roles: creative directors (n = 4), producers/project managers (n = 5), lead designers/animators (n = 6), developers/engineers (n = 4), and sound designers (n = 3). Participants had between 3 and 18 years of industry experience (mean ≈ 9 years).

4.3 Data Collection

Data triangulation was employed using three primary sources:

Semi-structured interviews: 22 in-depth interviews (45–90 minutes each) explored leadership behaviours, collaboration practices, decision-making processes, and project challenges. Interview protocols included open-ended prompts about leadership examples, conflict episodes, tool use, and lessons learned.

Participant observation: The researcher observed three active project teams (one at each organisation) for a combined total of 42 production-hours, attending meetings (pitch, review/dailies, sprint planning), design critiques, and informal interactions. Field notes captured interactional patterns, turn-taking, and artefacts used for coordination.

Document analysis: Project artefacts (briefs, storyboards, sprint boards, review notes, version histories) and communication logs (selected, with permission) were examined to contextualise practices and analyse governance mechanisms.

Data collection spanned four months, allowing observation of multiple project stages (pre-production, production, post-production).

4.4 Ethical Considerations

Approval was obtained from the relevant institutional review board. Participants provided informed consent; pseudonyms replaced real names, and organisations were anonymised (A, B, C). Sensitive project materials were redacted; participants could withdraw at any time. Data were securely stored and will be retained in line with institutional guidelines.

4.5 Data Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. NVivo (or manual coding) was used to support thematic coding. Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step approach to thematic analysis, the researcher (1) familiarized with the data, (2) generated initial codes (both deductive from theory and inductive from data), (3) searched for themes, (4) reviewed themes, (5) defined and named themes, and (6) produced the report. Coding emphasised patterns linking leadership behaviours to collaborative outcomes and contextual moderators.

Trustworthiness strategies included triangulation across data sources, member checking (participants reviewed summaries of findings), and maintaining an audit trail (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

5. Findings

Four principal themes emerged from data analysis. Each theme is supported by illustrative participant quotations and observations.

Theme 1: Adaptive/Transformational Leadership Encourages Creative Risk-Taking and Psychological Safety

Participants consistently identified leaders who balanced vision-setting with encouragement as catalysts for experimentation. In Organisation A (short film collective), the director’s practice of framing creative goals as explorative rather than evaluative led team members to propose unconventional approaches.

“Our director always says ‘try it, we can always throw it out later’ — that made it easier to bring half-baked ideas to the table.” — Animator, Org A

Observation of design critiques showed that leaders who acknowledged team uncertainties and praised effort cultivated environments where mistakes were reframed as learning opportunities. This practice aligned with Edmondson’s (1999) notion of psychological safety and with literature on transformational leadership fostering intrinsic motivation (Bass, 1985; Amabile, 1996).

Theme 2: Directive/Transactional Leadership Is Valuable under Technical Constraints and Tight Deadlines

In Organisation C (game studio), participants emphasised the importance of decisive, directive leadership during crunch periods. The lead producer’s clear allocation of tasks, strict milestone enforcement, and contingent reward systems (overtime compensation, bonus milestones) helped the team meet critical delivery targets without sacrificing technical coherence.

“When we had to hit the demo build, the lead simply said who does what — no debate. It felt harsher but got us to the finish line.” — Developer, Org C.

Participants noted that transactional behaviours (monitoring, feedback tied to outcomes) were not antithetical to creativity when applied selectively—particularly during integration phases demanding rigorous technical coordination.

Theme 3: Distributed Leadership and Role Complementarity Increase Resilience and Innovation

Across all sites, distributed leadership—where domain expertise carried decision authority—emerged as a recurrent pattern. For example, in Org B (digital agency), senior designers led visual decisions, while technical leads owned integration choices. This emergent, expertise-based distribution reduced bottlenecks and accelerated localised problem-solving.

“We don’t wait for the creative director to sign off on every micro-decision — leads have autonomy and that keeps work moving.” — Producer, Org B.

Role complementarity and clear decision domains reduced conflicting signals and built mutual respect; teams that practised shared leadership adapted faster to scope shifts.

Theme 4: Communication Practices and Shared Mental Models Mediate Leadership Effects

While leadership styles shaped climates and decision norms, the efficacy of those styles depended heavily on communication routines and the development of shared mental models. Teams with explicit artefacts — such as living storyboards, annotated dailies, playtest logs, and updated sprint boards — avoided misalignment even under distributed leadership.

“Our sprint board is basically our bible — if it’s on the board, everyone knows the state and rationale.” — Project Manager, Org B.

Conversely, teams lacking shared artefacts experienced role ambiguity and duplicated work, which writers and designers attributed to “noise” in leadership signalling.

6. Discussion

6.1 Synthesis with Theoretical Framework

Findings support a contingency view of leadership in multimedia production. Transformational/adaptive leadership fosters a climate for creativity and psychological safety (Edmondson, 1999; Bass, 1985), which aids ideation during pre-production and exploratory phases. Conversely, transactional/directive leadership is instrumental during integration and delivery phases where technical precision and schedule adherence are paramount (Yukl, 2013). Distributed leadership emerges as especially valuable in cross-disciplinary teams, aligning with literature that positions leadership as a shared social process in complex work (Gronn, 2002; Spillane, 2006).

Team processes—communication routines, artefacts, and shared mental models—act as mediators. Leadership styles are not uniformly effective; instead, their efficacy depends on whether they support the development and maintenance of these processes. This corroborates Hackman’s (2002) assertion that team enabling conditions (clear norms, supportive structures) determine team effectiveness.

6.2 Practical Implications

Stage-Sensitive Leadership: Leaders should consciously align their approach with project stages. Early stages benefit from visioning and intellectual stimulation; later stages require clarity, coordination, and monitoring.

Intentional Distribution of Authority: Empower domain experts to make decisions within clearly defined boundaries. Role clarity paired with autonomy reduces bottlenecks and preserves creative momentum.

Establish Shared Artefacts and Rituals: Implement structured but flexible review rituals (e.g., dailies, playtests) and living artefacts (versioned storyboards, annotated builds) to develop shared mental models.

Cultivate Psychological Safety: Leaders should model vulnerability, invite dissenting views, and normalise iterative failure to enable innovation.

Hybrid Leadership Competence: Training programs for creative leaders should include both soft skills (coaching, visioning) and hard skills (project management, pipeline understanding) to handle the mixed demands of multimedia projects.

6.3 Contribution to Literature

This study advances understanding by showing that leadership in multimedia contexts is contingent, hybrid, and often distributed. It integrates leadership theory with creativity and team-process perspectives, offering a nuanced model applicable to similar knowledge-and-arts-intensive domains.

6.4. Limitations

As with all qualitative research, findings are contextually bound and not statistically generalizable. The sample—three organisations and 22 participants—provides depth but limited breadth. Industries and organisational cultures vary widely; large-scale studios or broadcast networks might exhibit different dynamics. Participant self-reports are subject to recall bias; while triangulation mitigates this, future research could incorporate longitudinal, mixed-method designs and objective performance metrics (e.g., delivery timeliness, audience metrics).

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

Leadership in multimedia production requires flexibility, domain sensitivity, and an orientation toward enabling robust communication and shared understanding. No single leadership style is universally optimal. Rather, practitioners succeed when they:

- Adapt leadership approach to project phase (visionary during ideation; directive during integration).

- Build distributed decision systems grounded in role clarity and mutual trust.

- Institutionalise communication artefacts and rituals to build shared mental models.

- Prioritise psychological safety to maximise creative contributions.

For educators: integrate leadership modules in multimedia curricula, emphasising both creative facilitation and basic project management. For managers: develop leadership competencies through cross-training, enabling creative leads to understand pipelines and producers to appreciate creative processes.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. Westview Press.

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 421–449.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). SAGE.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behaviour and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. McGraw-Hill.

Goleman, D. (2000). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 78(2), 78–90.

Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451.

Hackman, J. R. (2002). Leading teams: Setting the stage for great performances. Harvard Business Review Press.

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal, 23(5), 26–34.

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organisation. Harvard Business School Press.

Keller, R. T. (2016). Cross-functional project groups in multiunit firms: More evidence on their performance consequences. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33(2), 100–112.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Mumford, M. D., Scott, G. M., Gaddis, B., & Strange, J. M. (2002). Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(6), 705–750.

Rigby, D. K., Sutherland, J., & Takeuchi, H. (2016). Embracing agile. Harvard Business Review, 94(5), 40–50.

Salas, E., Cooke, N. J., & Rosen, M. A. (2008). On teams, teamwork, and team performance: Discoveries and developments. Human Factors, 50(3), 540–547.

Sawyer, R. K. (2007). Group genius: The creative power of collaboration. Basic Books.

Spillane, J. P. (2006). Distributed leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399.

Tushman, M. L., & Nadler, D. A. (1978). Information processing as an integrating concept in organisational design. Academy of Management Review, 3(3), 613–624.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organisations (8th ed.). Pearson.

Zhu, W., Riggio, R. E., Avolio, B. J., & Sosik, J. J. (2018). The effect of leadership on follower job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 44(4), 1229–1259.